In a world gripped by constant striving, attachment, and anxiety, the idea of detachment can sound either liberating or cold. For some, it suggests freedom from suffering; for others, it feels like emotional abandonment. But what does detachment truly mean in the context of Buddhist wisdom?

As Spiritual Culture, we invite you to journey inward — to the very roots of what it means to live with deep compassion without clinging, to act with love without possessing, and to find peace without withdrawing from life.

This article explores the meaning of detachment in Buddhism — not as indifference, but as a path toward liberation, clarity, and true compassion. We will examine how detachment differs from apathy, how it supports freedom from suffering, and how it can be lived practically in everyday life. Along the way, we will turn to sacred texts, real-life metaphors, and inner reflections.

The Essence of Detachment in Buddhist Thought

Letting Go of Clinging, Not Love

At its core, detachment in Buddhism is not about withdrawing from life or feelings — it’s about liberation from clinging. The Buddha taught that attachment (taṇhā) is one of the main causes of suffering (dukkha). In the Four Noble Truths, the second truth identifies craving and clinging as the source of human sorrow.

“From craving arises sorrow, from craving arises fear; for one who is freed from craving, there is no sorrow — whence fear?”

— Dhammapada, verse 216

This craving manifests not just in desire for material things, but in the way we grip tightly to people, ideas, identities, and outcomes.

To be detached in the Buddhist sense is to love deeply without needing to possess, to engage fully without trying to control, and to allow change without resistance.

Detachment Is Presence, Not Absence

Many misunderstand detachment as a kind of numbness or coldness. But true detachment in Buddhism is the opposite — it invites us into deeper presence. We are no longer preoccupied with controlling or securing what we want. Instead, we meet the moment with clarity and care.

Detachment, then, is not about being distant — it is about being fully present, but free from bondage.

Detachment and the Middle Way

Beyond Extremes: Neither Clinging Nor Rejection

The Buddha’s teaching of the Middle Way emphasizes avoiding the extremes of indulgence and denial. Similarly, detachment is the middle path between being overly attached and being indifferent.

“Just as a musician tunes a string not too tight, not too loose — so should one walk the path.”

— Sutta Nipāta

This analogy reveals the subtlety of detachment. A string pulled too tight may snap — a metaphor for clinging. A string too loose loses sound — a symbol for indifference. The Middle Way calls for gentle balance, where detachment means not holding too tightly and not letting go carelessly.

The Three Poisons and the Role of Detachment

Craving, Aversion, and Delusion

Buddhism teaches that three root poisons — craving (rāga), aversion (dosa), and delusion (moha) — fuel the wheel of suffering (samsāra). Detachment directly counters the first poison: craving.

By practicing detachment, one gradually weakens the grip of craving, which leads to a more spacious, compassionate, and peaceful heart.

The Fire Metaphor: Letting Go to Cool the Mind

The Buddha often used fire as a metaphor. Our desires, he said, are like fires that burn the mind.

“The mind is burning… with the fire of lust, the fire of hatred, the fire of delusion.”

— Fire Sermon (Adittapariyaya Sutta)

Detachment is like water. It cools the fire. It doesn’t mean extinguishing our humanity, but purifying our relationship with desire, so we are not enslaved by it.

Detachment in Practice: Living the Teaching

Detachment Is Not Renunciation for All

While monastics practice physical renunciation, everyday laypeople are not expected to abandon relationships or responsibilities. Detachment for householders means learning to hold things lightly — to enjoy and care for life’s blessings without gripping them.

Everyday Examples of Detachment

- Parenting with Detachment: A parent provides love, guidance, and protection — but knows their child must grow, stumble, and choose their own path. Detachment allows the parent to support without suffocating.

- Loving without Possessing: In romantic relationships, detachment brings the maturity to love without ownership. It asks: Do I love this person for who they are — or for what they give me?

- Working without Ego: Detachment helps us give our best at work, yet accept outcomes beyond our control. It transforms labor into service, not a measure of self-worth.

Detachment and Compassion: Not Opposites

The Open Hand: A Metaphor of Love

Compassion and detachment are not in conflict. In fact, compassion deepens through detachment. Imagine two hands:

- A clenched fist holds tightly and restricts.

- An open hand gives freely, receives humbly, and lets go with peace.

Detachment is the open hand. It allows love to flow, rather than be trapped. It allows suffering to be witnessed, without being swallowed.

Bodhisattva Ideal: Detachment in Action

The Bodhisattva, a being who vows to serve all sentient beings before attaining full Buddhahood, embodies the union of compassion and detachment. They work tirelessly to ease suffering — but are free of self-centered grasping.

This ideal reveals that true spiritual detachment does not retreat from life. It embraces it with open-hearted clarity.

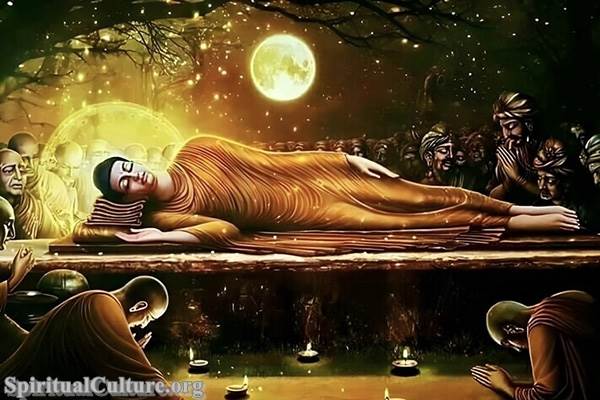

Detachment and Death: Learning to Let Go

Facing Impermanence with Grace

Perhaps nowhere is detachment more poignant than in the face of death. Buddhism teaches anicca — the truth of impermanence. Everything changes, everything passes.

To live with detachment is to live with the awareness of death — not in fear, but in reverence. It is to love without the illusion that anything or anyone is permanent.

“All conditioned things are impermanent — when one sees this with wisdom, one turns away from suffering.”

— Dhammapada, verse 277

Grieving with Detachment

Grief, too, can hold the fragrance of detachment. It means honoring the pain of loss without being consumed. It means holding sorrow tenderly, without trying to make it go away. It means allowing life to go on — not as betrayal, but as tribute to what was loved.

Detachment and Meditation: Cultivating Inner Stillness

Observing Without Grasping

In meditation, we learn to observe thoughts, feelings, and sensations without clinging or resisting. This non-reactive awareness is the heart of detachment.

When a thought arises — “I should have done better” — we learn to see it, not become it. When joy arises, we savor it — but let it pass like a cloud.

Equanimity (Upekkhā)

One of the Four Immeasurables (Brahmavihārās) in Buddhism is upekkhā — equanimity. It is the serene wisdom that sees all beings with balance. Not coldness, but the insight that all things rise and fall, and our peace lies in that understanding.

Reflect and Reimagine

Detachment, in its true Buddhist sense, is a path to freedom, not disconnection. It is an invitation to love more purely, live more fully, and suffer less needlessly. It teaches us to show up to life — not gripping it, but flowing with it.

What might change if we lived with less grasping and more grace?

What burdens might lift if we could let go without giving up?

What new love might arise if we could hold others with open hands?

As Spiritual Culture, we invite you to explore detachment not as the end of love, but as its purification. Let it be your doorway into peace — and your mirror into deeper truth.

Let go. But stay present.

Care deeply. But don’t cling.

Be in the world. But not bound by it.

This is the way of detachment. This is the way of freedom.

The Meaning of Detachment in Buddhism

Letting go without losing love: Discover the spiritual strength of detachment in the heart of Buddhist wisdom.

In a world gripped by constant striving, attachment, and anxiety, the idea of detachment can sound either liberating or cold. For some, it suggests freedom from suffering; for others, it feels like emotional abandonment. But what does detachment truly mean in the context of Buddhist wisdom?

As Spiritual Culture, we invite you to journey inward — to the very roots of what it means to live with deep compassion without clinging, to act with love without possessing, and to find peace without withdrawing from life.

This article explores the meaning of detachment in Buddhism — not as indifference, but as a path toward liberation, clarity, and true compassion. We will examine how detachment differs from apathy, how it supports freedom from suffering, and how it can be lived practically in everyday life. Along the way, we will turn to sacred texts, real-life metaphors, and inner reflections.

The Essence of Detachment in Buddhist Thought

Letting Go of Clinging, Not Love

At its core, detachment in Buddhism is not about withdrawing from life or feelings — it’s about liberation from clinging. The Buddha taught that attachment (taṇhā) is one of the main causes of suffering (dukkha). In the Four Noble Truths, the second truth identifies craving and clinging as the source of human sorrow.

“From craving arises sorrow, from craving arises fear; for one who is freed from craving, there is no sorrow — whence fear?”

— Dhammapada, verse 216

This craving manifests not just in desire for material things, but in the way we grip tightly to people, ideas, identities, and outcomes.

To be detached in the Buddhist sense is to love deeply without needing to possess, to engage fully without trying to control, and to allow change without resistance.

Detachment Is Presence, Not Absence

Many misunderstand detachment as a kind of numbness or coldness. But true detachment in Buddhism is the opposite — it invites us into deeper presence. We are no longer preoccupied with controlling or securing what we want. Instead, we meet the moment with clarity and care.

Detachment, then, is not about being distant — it is about being fully present, but free from bondage.

Detachment and the Middle Way

Beyond Extremes: Neither Clinging Nor Rejection

The Buddha’s teaching of the Middle Way emphasizes avoiding the extremes of indulgence and denial. Similarly, detachment is the middle path between being overly attached and being indifferent.

“Just as a musician tunes a string not too tight, not too loose — so should one walk the path.”

— Sutta Nipāta

This analogy reveals the subtlety of detachment. A string pulled too tight may snap — a metaphor for clinging. A string too loose loses sound — a symbol for indifference. The Middle Way calls for gentle balance, where detachment means not holding too tightly and not letting go carelessly.

The Three Poisons and the Role of Detachment

Craving, Aversion, and Delusion

Buddhism teaches that three root poisons — craving (rāga), aversion (dosa), and delusion (moha) — fuel the wheel of suffering (samsāra). Detachment directly counters the first poison: craving.

By practicing detachment, one gradually weakens the grip of craving, which leads to a more spacious, compassionate, and peaceful heart.

The Fire Metaphor: Letting Go to Cool the Mind

The Buddha often used fire as a metaphor. Our desires, he said, are like fires that burn the mind.

“The mind is burning… with the fire of lust, the fire of hatred, the fire of delusion.”

— Fire Sermon (Adittapariyaya Sutta)

Detachment is like water. It cools the fire. It doesn’t mean extinguishing our humanity, but purifying our relationship with desire, so we are not enslaved by it.

Detachment in Practice: Living the Teaching

Detachment Is Not Renunciation for All

While monastics practice physical renunciation, everyday laypeople are not expected to abandon relationships or responsibilities. Detachment for householders means learning to hold things lightly — to enjoy and care for life’s blessings without gripping them.

Everyday Examples of Detachment

- Parenting with Detachment: A parent provides love, guidance, and protection — but knows their child must grow, stumble, and choose their own path. Detachment allows the parent to support without suffocating.

- Loving without Possessing: In romantic relationships, detachment brings the maturity to love without ownership. It asks: Do I love this person for who they are — or for what they give me?

- Working without Ego: Detachment helps us give our best at work, yet accept outcomes beyond our control. It transforms labor into service, not a measure of self-worth.

Detachment and Compassion: Not Opposites

The Open Hand: A Metaphor of Love

Compassion and detachment are not in conflict. In fact, compassion deepens through detachment. Imagine two hands:

- A clenched fist holds tightly and restricts.

- An open hand gives freely, receives humbly, and lets go with peace.

Detachment is the open hand. It allows love to flow, rather than be trapped. It allows suffering to be witnessed, without being swallowed.

Bodhisattva Ideal: Detachment in Action

The Bodhisattva, a being who vows to serve all sentient beings before attaining full Buddhahood, embodies the union of compassion and detachment. They work tirelessly to ease suffering — but are free of self-centered grasping.

This ideal reveals that true spiritual detachment does not retreat from life. It embraces it with open-hearted clarity.

Detachment and Death: Learning to Let Go

Facing Impermanence with Grace

Perhaps nowhere is detachment more poignant than in the face of death. Buddhism teaches anicca — the truth of impermanence. Everything changes, everything passes.

To live with detachment is to live with the awareness of death — not in fear, but in reverence. It is to love without the illusion that anything or anyone is permanent.

“All conditioned things are impermanent — when one sees this with wisdom, one turns away from suffering.”

— Dhammapada, verse 277

Grieving with Detachment

Grief, too, can hold the fragrance of detachment. It means honoring the pain of loss without being consumed. It means holding sorrow tenderly, without trying to make it go away. It means allowing life to go on — not as betrayal, but as tribute to what was loved.

Detachment and Meditation: Cultivating Inner Stillness

Observing Without Grasping

In meditation, we learn to observe thoughts, feelings, and sensations without clinging or resisting. This non-reactive awareness is the heart of detachment.

When a thought arises — “I should have done better” — we learn to see it, not become it. When joy arises, we savor it — but let it pass like a cloud.

Equanimity (Upekkhā)

One of the Four Immeasurables (Brahmavihārās) in Buddhism is upekkhā — equanimity. It is the serene wisdom that sees all beings with balance. Not coldness, but the insight that all things rise and fall, and our peace lies in that understanding.

Reflect and Reimagine

Detachment, in its true Buddhist sense, is a path to freedom, not disconnection. It is an invitation to love more purely, live more fully, and suffer less needlessly. It teaches us to show up to life — not gripping it, but flowing with it.

What might change if we lived with less grasping and more grace?

What burdens might lift if we could let go without giving up?

What new love might arise if we could hold others with open hands?

As Spiritual Culture, we invite you to explore detachment not as the end of love, but as its purification. Let it be your doorway into peace — and your mirror into deeper truth.

Let go. But stay present.

Care deeply. But don’t cling.

Be in the world. But not bound by it.

This is the way of detachment. This is the way of freedom.