The Gregorian calendar, the calendar system most widely used today, is a modification of the Julian calendar that addresses its inaccuracies in measuring the length of the solar year.

In this article, Spiritual Culture delves into the historical context of calendar development, key figures involved in its invention, the important Papal Bull that enacted it, the mechanics of leap years under this system, its adoption worldwide, its impact on religious observances, and its modern relevance.

Historical Context of Calendar Development

Influence of the Julian Calendar

The Julian calendar, introduced by Julius Caesar in 45 BC, was a revolutionary reform of the Roman calendar. It established a solar calendar of 365.25 days per year, achieved by including an extra day every four years, creating what we now call a leap year. While innovative, the Julian calendar did not accurately reflect the solar year, which is approximately 365.2425 days. This discrepancy, though seemingly small, accumulated over centuries, causing significant misalignment with the seasons.

The Julian calendar’s flaws became increasingly evident by the late Middle Ages, as the misalignment with the equinoxes and solstices affected agricultural cycles and religious observances, especially Easter, which depends on the timing of the spring equinox.

Need for Reform in the 16th Century

By the 16th century, the inaccuracies of the Julian calendar had resulted in the date of the spring equinox shifting from its original position around March 21 to around March 11. This drift posed serious issues for the Church and society, emphasizing the pressing need for a calendar reform. Moreover, as exploration and trade expanded, accurate date-keeping became essential for synchronization of events across different regions and countries.

In this context, Pope Gregory XIII recognized the urgent need for change, paving the way for the introduction of the Gregorian calendar.

Key Figures in the Invention

Role of Pope Gregory XIII

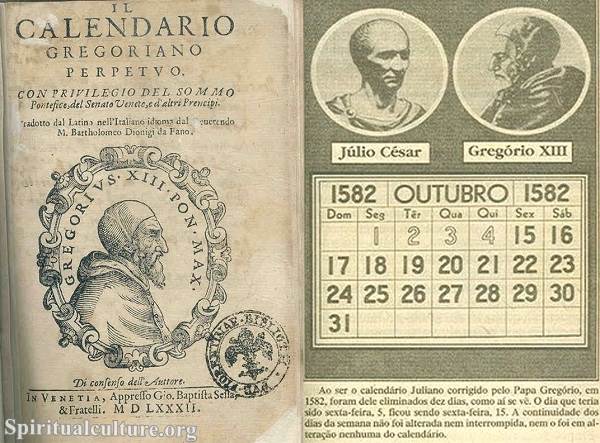

Pope Gregory XIII, born Ugo Boncompagni in 1502, played a pivotal role in the Gregorian calendar’s development. Elected pope in 1572, he was determined to correct the calendar errors persisting under the Julian system. This determination was not merely administrative; it had theological implications, particularly concerning the timing of Easter.

Understanding the need for precise timekeeping in relation to the agricultural calendar and ecclesiastical observances, Pope Gregory took significant steps towards reform. He commissioned a committee of astronomers and scholars to evaluate the Julian calendar’s shortcomings and propose solutions.

Contributions of Astronomers and Scholars

Among the notable figures collaborating with Pope Gregory XIII were Christopher Clavius, an esteemed Jesuit astronomer, and physician. Clavius’s influential insights into the workings of the calendar provided invaluable support to the Gregorian reform. His calculations revealed the need for a more accurate system to maintain the alignment of the calendar with astronomical events.

The committee’s recommendations based on Clavius’s work, coupled with other scholarly contributions, led to the creation of the Gregorian calendar, which sought to achieve better harmony between the calendar year and the solar year.

The Papal Bull Inter Gravissimas

Date of Issuance and Its Importance

On February 24, 1582, Pope Gregory XIII issued the papal bull Inter Gravissimas, officially instituting the Gregorian calendar. This document not only detailed the reforms necessary to correct the calendar but also emphasized their theological foundations. The issuing of the bull marked a historic pivot in how time was organized in the Western world.

Changes Introduced by the Bull

Inter Gravissimas comprised several key reforms:

- Calendar Adjustment: Ten days were omitted from the calendar to realign the calendar with the solar year. Thus, October 4, 1582, was followed by October 15, 1582.

- Leap Year Reform: The Gregorian calendar refined the leap year system, stipulating:

- A year is a leap year if it is divisible by 4.

- However, years divisible by 100 are not leap years unless they are also divisible by 400.

These systematic changes were designed to keep the calendar year within a day of the solar year.

Mechanism of Leap Years

Difference from the Julian Calendar Leap Year System

The leap year mechanism in the Julian calendar was much simpler, allowing every fourth year to be a leap year without exception. This system resulted in an annual average of 365.25 days, causing the calendar to lose approximately 11 minutes per year compared to the solar year. Over centuries, this discrepancy led to the misalignment of the calendar with seasons and equinoxes.

Conversely, the Gregorian calendar’s adjusted leap year rules reduce the average year to 365.2425 days—much closer to the actual solar year. This refined calculation didn’t just improve seasonal accuracy but also represented a more sophisticated understanding of astronomy at that time.

Calculation of Leap Years in the Gregorian Calendar

The calculation method establishes a more nuanced approach:

- If a year is divisible by 4, it is a leap year.

- If the year is divisible by 100, it is not a leap year.

- However, if the year is also divisible by 400, it remains a leap year.

For example, 1600 and 2000 are leap years, but 1700, 1800, and 1900 are not. This system significantly minimizes the discrepancies over long periods, ensuring more accurate alignment with seasonal changes.

Adoption Throughout the World

Initial Adoption by Catholic Countries

The adoption of the Gregorian calendar began swiftly in predominantly Catholic countries. The Catholic Church’s influence in Europe facilitated a relatively smooth transition. Countries such as Spain, Portugal, Italy, and France adopted the new calendar almost immediately after its announcement in 1582.

Spread to Protestant and Non-Christian Countries

The adoption process, however, was not universally immediate. Various Protestant nations were initially resistant to a calendar instituted by a papal decree, viewing it as an act reflecting Catholic authority. England, for instance, did not adopt the Gregorian calendar until 1752, while Russia held out until the 20th century, maintaining the Julian calendar for most of its religious and civil observances until the Soviet government’s reform in 1918.

This gradual adoption illustrates how sociopolitical and religious contexts can significantly influence calendrical systems. Over the years, the Gregorian calendar spread to non-Christian countries, especially through colonial influences and globalization.

Impact on Religious Observances

Effects on the Date of Easter

One of the most profound effects of implementing the Gregorian calendar was its impact on the calculation of Easter. Easter is determined by a lunisolar calendar, relying on the timing of the spring equinox and the lunar phases. The reforms corrected the drift that the Julian calendar had introduced into the date of Easter.

The agreement established by the Council of Nicaea in 325 A.D.—that Easter should be observed on the first Sunday following the first full moon after the vernal equinox—continued to demand accuracy. By rectifying the equinox’s date through the Gregorian reform, the timing of Easter became more consistent across Christian denominations that embraced the new calendar.

Changes in Liturgical Calendars

Along with Easter, numerous other religious observances were affected by the transition to the Gregorian calendar. The alignment of feast days, rituals, and other significant events underwent changes as churches shifted their liturgical calendars to accommodate the new timing.

For instance, many saints’ feast days that had earlier been calculated according to Julian reckoning now fell on different dates. This reform created a unified standard for Catholics, albeit divisive for those communities that upheld the Julian calendar.

Modern Relevance and Usage

Current Status of the Gregorian Calendar

Today, the Gregorian calendar remains the most widely used civil calendar in the world, with many countries following it for both secular and religious purposes. It structures our daily lives, marking everything from historical events to contemporary celebrations, economic activities, and astronomical phenomena.

Comparison with Other Calendar Systems

While the Gregorian calendar dominates, other calendars still hold significant cultural and religious importance, such as the Islamic lunar calendar, the Hebrew calendar, and various regional calendars. For instance, while several cultures might observe Ramadan, Rosh Hashanah, or Vesak according to their respective calendars, the Gregorian calendar provides a common framework for international communication and scheduling.

The coexistence of various calendars showcases the intricate tapestry of human culture and the ways in which diverse communities mark time, illustrating the intersection of astronomy, religion, and culture throughout history.

Conclusion

In summary, the Gregorian calendar, invented under the auspices of Pope Gregory XIII, traces its roots back to the need for accuracy in timekeeping that the Julian calendar could no longer satisfy. Through the influential contributions of astronomers and scholars, the papal bull Inter Gravissimas laid the groundwork for a calendar that deeply resonated with both ecclesiastical and civil life.

Its adoption over the centuries reflects the complex interplay of politics, religion, and culture across the globe. Understanding who invented the Gregorian calendar not only illuminates our comprehension of timekeeping but also helps us appreciate the historical contexts and cultural narratives that shape our modern experience of time today.