The table is set, the bread is broken, the cup is lifted — but what does it mean?

Across Protestant traditions, Communion, also known as the Lord’s Supper, is one of the most sacred moments in the rhythm of worship. While its outward form may vary, its spiritual essence remains a central thread in Christian life: a shared meal that speaks of sacrifice, remembrance, and hope.

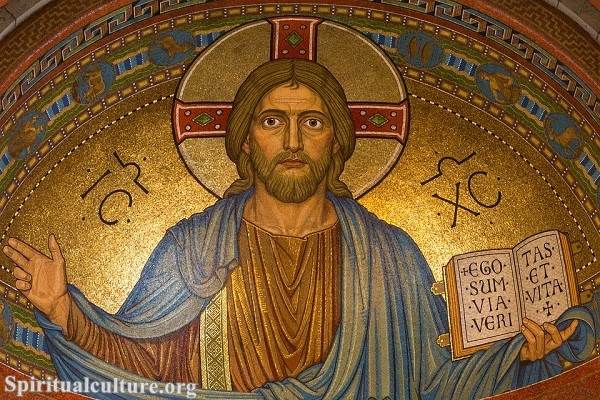

As Spiritual Culture, we invite you into a deeper reflection on what this act means for millions of believers today. Why do Protestants observe Communion? What do the bread and cup represent? How does this sacred act connect us to Christ — and to each other?

Let us journey through the meaning of Communion, not just as a doctrine, but as a divine invitation.

Communion in Protestantism: An Overview

A Symbolic Act of Obedience and Remembrance

At the heart of Communion is Jesus’ command: “Do this in remembrance of Me” (Luke 22:19). In Protestant theology, the Lord’s Supper is primarily a memorial — a symbolic act where believers recall Jesus’ death and resurrection with reverence.

Unlike Catholic or Orthodox traditions, which often emphasize the real presence of Christ in the elements (through transubstantiation or sacramental mystery), most Protestants view Communion as a powerful symbol, not a literal transformation.

The Two Elements: Bread and Cup

- The Bread represents the body of Christ, broken for humanity.

- The Cup (wine or grape juice) represents His blood, poured out for the forgiveness of sins.

Together, they form a vivid picture of the Gospel: sacrifice, atonement, and new covenant.

The Origins: Jesus at the Table

The Last Supper and Its Significance

The foundation of Communion lies in the Last Supper, when Jesus gathered His disciples the night before His crucifixion. In that sacred moment, He broke bread and shared wine, saying:

“This is My body, given for you… This cup is the new covenant in My blood…”

— Luke 22:19–20

Jesus redefined the Passover meal, turning it into a new covenant celebration — not just a remembrance of Israel’s deliverance from Egypt, but a deeper deliverance from sin and death.

A New Covenant of Grace

The word covenant in Scripture denotes a sacred promise. In Communion, believers participate in this new covenant — one not based on law, but on grace.

Protestant Views on Communion: Diverse Yet Rooted in Christ

Lutheran Tradition: The Real Presence (Consubstantiation)

Martin Luther held that Christ is truly present “in, with, and under” the elements. Though not transformed into literal flesh and blood, the bread and wine are mysteriously united with Christ’s body and blood.

“The Word must be present for the sacrament to be valid. Where the Word is, there is also Christ.”

— Martin Luther

Reformed and Presbyterian Traditions: Spiritual Presence

Reformers like John Calvin taught that Jesus is spiritually present in the elements. Through faith and the work of the Holy Spirit, believers are lifted spiritually to commune with Christ.

This view upholds the sacredness of the act, while avoiding the idea of physical transformation.

Baptist and Evangelical Traditions: Memorial and Fellowship

Many Baptists and Evangelicals see Communion as a symbolic act of remembrance — deeply meaningful, yet non-sacramental. It’s a declaration of faith, unity, and personal reflection.

In these traditions, emphasis is placed on the individual’s heart: “Let a person examine himself, then, and so eat…” (1 Corinthians 11:28).

Why Communion Matters Spiritually

A Moment of Sacred Remembrance

In a world of distractions and division, Communion calls us back to the cross — to remember Christ’s suffering, to cherish His love, and to embrace the hope of resurrection.

It is a holy pause in the flow of worship, where time seems to stop and the soul reflects.

A Communal Act of Unity

The word “Communion” implies togetherness — not just with Christ, but with one another. As Paul writes:

“Because there is one loaf, we, who are many, are one body…”

— 1 Corinthians 10:17

Across denominations, languages, and cultures, believers share this sacred table, affirming that in Christ, we are one family.

A Declaration of Hope

Every time we take the bread and cup, we proclaim:

“The Lord’s death until He comes.”

— 1 Corinthians 11:26

Communion points forward — to the promise of Christ’s return and the eternal feast in the Kingdom of God (Revelation 19:9).

The Practice of Communion: Forms and Frequency

How Often Do Protestants Take Communion?

The frequency varies by denomination:

- Lutherans and Anglicans often celebrate weekly or monthly.

- Reformed churches may offer Communion monthly or quarterly.

- Baptists and Evangelicals vary — from weekly to a few times a year.

Each tradition chooses its rhythm, but the heart remains the same: Christ remembered, honored, and worshipped.

Who Can Participate?

Most Protestant churches practice open Communion for baptized believers — welcoming all who profess faith in Christ. However, some congregations may ask visitors to reflect or refrain if not yet part of the faith.

Communion and the Inner Life

Examining the Heart

Paul’s words in 1 Corinthians 11 urge believers to come to the table with reverence and reflection — not casually, but thoughtfully:

“Whoever eats… in an unworthy manner… will be guilty concerning the body and blood of the Lord.”

Communion invites confession, repentance, and renewal. It is a sacred encounter with grace.

Nourishing the Soul

Though the bread and cup are physical, they point to a spiritual nourishment — a reminder that just as the body needs food, the soul needs Christ.

“I am the bread of life. Whoever comes to Me will never go hungry…”

— John 6:35

Communion strengthens faith, renews love, and deepens connection with the living Christ.

How Communion Shapes Protestant Worship and Culture

Simplicity and Sacredness

Unlike elaborate liturgies in other traditions, many Protestant Communions are marked by simplicity: a table, scripture, quiet prayer, the passing of elements.

Yet within this simplicity lies profound beauty — a sense of sacred nearness and holy intimacy.

A Witness to the World

Communion is not only inward-facing. It also speaks outwardly. It declares:

- Christ’s death and resurrection

- The unity of the Church

- The hope of the Gospel

In a fragmented world, Communion says: “We belong to something greater.”

The Mystery That Unites

Though Protestants may disagree on theology, style, or frequency, Communion remains a shared mystery — a sacred thread binding hearts to Christ and to one another.

It is more than tradition. More than symbol. It is a space where heaven meets earth, past meets present, and brokenness meets healing.

“Come, for all is now ready.”

— Luke 14:17

Reflect and Reimagine

The meaning of Communion in Protestant traditions is not locked in doctrine alone — it is lived at the table of grace, Sunday after Sunday, soul after soul.

To partake in Communion is to say:

- I remember what Jesus did.

- I believe in who He is.

- I belong to His people.

- I await His return.

Whether you receive it in a cathedral, a country chapel, or a home gathering, the call is the same: “Do this in remembrance of Me.”

So come with a humble heart.

Come with hunger for grace.

Come and be filled.

— With you at the table,

Spiritual Culture